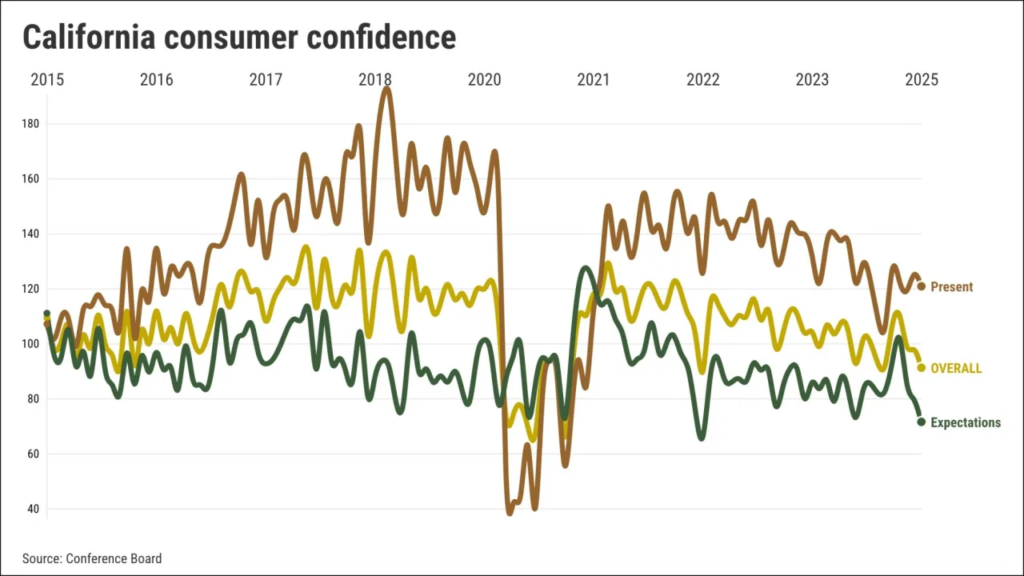

An index tracking statewide expectations reports that consumer confidence in California fell 7% in January—marking a 30-month record low.

Californians are worried about their financial futures. That sentiment was already widely felt, given the Golden State’s high cost of living—largely due to record housing unaffordability, high taxes, steep auto insurance premiums, and inflated grocery prices—but now it can be proven quantitatively.

The Conference Board recently published its January consumer confidence indexes, a series of monthly reports which track “consumer attitudes, buying intentions, vacation plans and consumer expectations for inflation, stock prices and interest rates.” In California, the statewide expectations index 7% last month, which itself is down 30% since October.

Since the Board started indexing consumer confidence in 2007, optimism on a national level has risen by about 13%. However, if one were to take the average from every month during the past 18 years, that total would fall within one percentage point of where California stands today—at a 30-month low. This shows us that, as a whole, confidence in the United States has increased over the last two decades while confidence in California has made almost no substantial progress.

As of March 2024, overall prices in California have gone up nearly 20% since 2020. Sarah Bohn, director of the Public Policy Institute of the California Economic Policy Center, has compared wages with the massive inflation prices: “Wages only grew 15% than before the pandemic. On paper, that looks amazing, like a $5-an-hour increase. But after inflation, it feels like a pay cut — I calculated that it’s like a $1.25-an-hour cut.”

California also has the nation’s highest rate of function poverty at around 15.4%, according to Census Bureau data. The state’s California’s troubling housing is a major contributing factor, as is the broader economy.

“The question marks have shifted to being more about the economy, how it’s going to hold up, what’s going to happen with inflation,” said Jordan Levine, chief economist at the California Association of Realtors. “I think the macro (issues) are going to have an impact on the regional housing market.”

When pandemic aid programs ended, this had a massive effect on families that had relied on that aid to provide food for their children. With wages that can’t keep up with inflation and certain living costs, California consumers are forced to make difficult choices at the grocery store. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported at the end of 2024 that in the Los Angeles area, overall food prices rose 3.1% between December 2023 and December 2024. Grocery prices for meat, poultry, fish and eggs rose 4%, and restaurant prices rose 4.1%. All of those values follow additional year-to-year inflationary growth going back to 2021 and, in some cases, the start of the 2020 pandemic.

COVID-19 also led to a sharp increase in auto insurance rates. While these rates are up nationwide as a result of pandemic era supply chain issues only just correcting, they are particularly bad in California.

“Data from the insurance department shows rate hikes ranging from 4% to double-digit percentages, with the highest auto premiums approved so far being a 62% increase from online car-insurance company Root Insurance, and a 65% increase for motorcycle insurance from Geico,” writes economic reporter Levi Sumagaysay for CalMatters. “The approved rate increases so far have averaged 13.2%, compared with an average of 10.6% in 2019, before the pandemic. In 2018, the average approved rate increase was 6.8%.”

Another interesting correlation is that, of the states measured, the most financially uncertain Americans seem to live in states where President Donald Trump did not win the majority of votes during the November election. Along with California, New York and Illinois’ confidence levels fell in January and have continued to fall since October. Of the states surveyed that did go for Trump, only Pennsylvania was below pre-election levels. Therefore, it can be reasonably assumed that voters who were unhappy with the results of last year’s election are experiencing higher levels of unease about the economy.

That—or they happen to inhabit some of the nation’s most expensive, overregulated, and tax-heavy states. Both assessments would true. While California and New York teeter back and forth between 2nd, 3rd, and 4th place for highest cost of living (with Hawaii consistently sitting in 1st), Illinois has the distinguished dishonor of placing dead last in fiscal stability. New York is notable in that it remains an overall fairly optimistic state—just one that has continued to plummet in the wake of Trump’s election.

“Now, you don’t need an index to know liberal California and conservative Trump aren’t a great mix,” writes Southern California News Group business columnist Jonathan Lansner. “Nobody knows the long-range outcomes of his plans for large-scale deportations of undocumented residents, potential tariff wars with trading partners, giant tax cuts or possible cuts in government benefits. Those unknowns are now added to existing California anxieties, which include an iffy job market, costly living expenses, lofty interest rates and the Los Angeles wildfires.”

However, all four of the aforementioned states are deep blue and have enjoyed solid Democrat legislative majorities for decades—long before Trump, MAGA, or the November 2024 elections. Conversely, Michigan—which went for Trump in 2016 and 2024, but not in 2020) is currently the most optimistic state (of those surveyed) at 36% above its norm.

So, perhaps, it says more about the uncertainty of the Trump administration’s economic ideals and more about the pitfalls of political and ideological insulation. Quantitative date—not idle speculation—suggests that one party rule has not yet helped Hawaii, California, New York, or Illinois combat fiscal instability, housing unaffordability, or economic uncertainty.

Perhaps the solution to these financial problems lies in bipartisanship and working in collaboration with, rather than solely against, the new administration and the other side of the proverbial aisle.